Effective leadership and proper logistics are mandatory for victory in any military campaign. If one of these variables fails, the army is steadily weakened and, eventually, eliminated. History is rife with examples of campaigns gone wrong through ignorance of these rules. The First Crusade provides a good example of how a military campaign on every level should have failed. Understanding the logistics side of the First Crusade is challenging with the available sources. I focused on the subject for the last three months, utilizing the work of primary sources close to the events and experts on the subject, like John France, Gregory Bell, and John Haldon. I began by trying to answer the simple question, “How did these guys feed themselves?” But I got lost in the twists and turns, which is easy to do, I found, when delving into the Crusades. What follows is an amateur attempt at answering that question.

The Writers of the First Crusade

The First Crusade is unique because many of the primary source authors accompanied the marching columns on the campaign. They were eyewitness to the events. The author of the Gesta Francorum marched with Bohemund’s column, Fulcher of Chartres was part of Robert of Normandy and Stephen of Blois’s north French contingent, and Raymond of Aguilers was a chaplain with Raymond of Toulouse and the Provencal south French. Peter Tudebode was a Poitevin priest who was on the First Crusade and possibly served with the forces of Raymond. While Ralph of Caen was a member of first Bohemond, then Tancred’s following. The writers generally exaggerate numbers and avoid the topic of logistics, but their testimony is still valid.

The Latin West

The Crusaders came from the Latin West and became collectively known as the Franks by the Muslims and Byzantines. One culture that made up a majority of the first crusaders was the Normans. The Normans were not a novel group to the Eastern world. They entered Italy in the 11th century and served as mercenaries for various Lombard princes. By the 1050s, the Normans began serving in Byzantine formations in Syria and Bulgaria, including a standing garrison in Anatolia. (Decker, 173) Around this time, the Byzantines began to refer to the Normans as “Franks.” The Normans began their conquest of southern Italy in the 1040s, carving out permanent counties in the south. The invasion brought them into conflict with the Byzantines, who held territory in south Italy. By 1091, the Normans conquered Sicily from minor Muslim dynasts, elevating the Norman Hauteville dynasty to the hegemon of southern Italy. (Decker, 175)

In 1081, Robert Guiscard, one of the leaders of the Hauteville clan in southern Italy, led a Norman invasion into the Byzantine Balkans. During the conflict, the Normans beat the Byzantine emperor, Alexios in battle several times until things went awry in Italy, and Robert had to depart, leaving Bohemond in charge. Alexios eventually defeated Bohemond’s army through subterfuge. However, the Normans would be a continual thorn in the side of the empire before and after the First Crusade. Over the next century, two more major Norman invasions pierced imperial borders. The constant friction between the Normans and Byzantines infused the western Latins into Anatolian affairs. Alexios would remember that experience when pushed against the wall by the Seljuq Turks towards the end of the century. (Kaldellis, 330)

Armies of the East

The opposing side was fractured between the Fatimids, based in Egypt, and the Seljuq Turks, centered in Baghdad. The Seljuq Turks can further be broken down into the Seljuq Turks of Rum, who were the first adversaries encountered by the Crusaders. They were outstanding horsemen, but their strength weakened with the fall of strong leadership. Ibn al-Qalanisi describes an old militia system in which every man listed on the tribal registers received a pension from the public treasury but was always on call for military expeditions. Over time, this system evolved into the formation of standing armies.

Military Transformation in the 9th Century

In the ninth century, most of the eastern Islamic states underwent a significant military transformation. Their forces were composed primarily of salaried guards, mainly slaves who were purchased, obtained as tribute, or inherited by the ruling prince. These guards formed the backbone of the standing army, and they were the first to receive state funding. According to Qalanisi, the majority of these soldiers were Turks from Central Asia but also included Slavs from Eastern Europe, Greeks, and captives from Anatolia, Armenia, and Georgia. All were mounted and skilled in shooting bows from horseback. For close combat, they were equipped with lances and swords. (Qalanisi, 32)

The Abbasids controlled most of the Middle East from the mid-eighth to the mid-thirteenth century, taking over from the Umayyads. They governed several specialized offices or ministries known as diwans, which were overseen by a vizier. Small land grants, or iqta, were allocated to draw soldiers for a military component. (France, 200) The caliphs and their governors maintained substantial Turkish tribal forces, such as those under Yaghisiyan, governor of Antioch, filling his ranks with manpower squeezed from the iqtas. These mamluks formed core personal followings, which became the go-to combat element for the princelings and emirs of Syria.

Fall of Strong Leadership

The Sultan could also rely on military support from various allies in regions such as Syria, Mesopotamia, Iran, and further east. The system was made possible by the intricate inner workings of the administrative structure in Baghdad. Nizam al-Mulk was the vizier of the Seljuqs in the late 11th century, one of their strongest leaders. His fall and the fall of leaders similar to him, like Malik Shah, was one of the reasons the Crusaders cut through the Holy Land with such ease. Nizam al-Mulk was directly involved in the management of his army. For example, he mandated that local governments maintain fodder stocks within the settlements for military use. (France, 202)

Standing Armies

The standing army of mounted guards was called an askar, while the individual trooper was called an askari, or, in other sources, ghulam. The askar had a regular promotion system according to length-in-service, and they distinguished themselves through unique dress features. Qalanisi referred to the commander of a regiment as an amir, while the higher-up officers and commander-in-chief were called hajib. Commanders were selected from the ruler’s private guard and usually held additional court offices. In turn, the officers who rose in rank were encouraged to purchase their own private guard of slaves, which were enrolled in the general body of the askar once their master died. They usually formed a separate regiment named after their former owner. (33, Qalanisi)

Lords of Northern Syria

Usama Ibn Munqidh was a young Muslim warrior born into semi-royalty at the castle of Shaizar in northern Syria. In his writing, The Book of Contemplation, Munqidh relates his experience fighting the Franks on the front lines of his home. He provides an eyewitness account of how the nephew of the lord of a castle, kind of like a staff officer, would recruit, march, and supply themselves on what he would call an adventure. Of all the primary sources I perused, Munqidh was my favorite. He was specific with his writing, leaving nothing to the imagination. “By the following Monday, I had recruited 860 horsemen.” (Munqidh, 24) His book is a great source to witness the interaction between East and West post-First Crusade and includes everything from lion hunts to court intrigues with the Fatimids and Seljuqs.

Western Leadership

The First Crusade leadership structure diverted from the standard leadership hierarchies in previous military campaigns. The leaders from the west included Hugh of Vermandois, brother to the king of France; Robert Curthose, eldest son of William of Normandy; Robert II of Flanders; Godfrey IV, duke of Lower Lotharingia, and lord of many territories within that area; Bohemond I, lord of Taranto and son of Robert Guiscard; Stephen of Blois; Count Raymond IV of Toulouse and Adhemar, Bishop of Le Puy. Tatikios, a Byzantine commander, isn’t mentioned in the primary sources as being present at any of the councils, but he was probably a participant until Antioch. (Kostic, 16) Adhemar of Le Puy emerges as the primary spiritual leader, unanimously chosen by the princes and pilgrims for his suitability in secular and divine matters. Raymond of Aguilers and Ralph of Caen refer to him as a “second Moses.” But it’s an ambiguous role; Adhemar didn’t set strategy or run logistics. (Kostic, 245) He kept the princes in line and got them to work together using his authority as papal legate and spiritual lead. In addition, he led services and distributed alms and tithes of captured booty to the poor. (Kostic, 248)

Councils and Assemblies

Military leadership was organized and directed during the campaign through councils and assemblies. If there was time before a great battle, the Crusaders sometimes selected a temporary leader, like Bohemond’s selection at the Battle of Antioch. Stephen of Blois wrote to his wife Adela around March 1098, informing her of his selection as leader at Antioch. Even though it wasn’t long after that date when he deserted the Crusaders besieged in the city. (SofB) Each contingent had its own council. The Gesta Francorum says Bohemund called a council of his people to keep them from plundering the Byzantine countryside. (Dass, 8) Bishops were an essential part of the council. Nine bishops served the various contingents by the siege of Antioch. Eight traveled from Western Europe, including Peter of Narbonne, who rose to become the Bishop of Albara around September 25, 1098. (Kostic, 18)

Councils met to make even simple decisions. In December 1096, Duke Godfrey held a council with the primores, noble members of his force, before responding to an envoy from the Byzantine emperor. (Kostic, 15) When the Crusaders reached Antioch in 1097, Raymond held a council of the south French contingent to send five hundred knights to reconnoiter the Turkish garrison ahead of them. By 1098, and the siege of Antioch, Raymond needed to encourage his knights to defend the small detachments going out to forage and called a council with his magnates and Adhemar. After the Crusaders took Antioch, Ralph of Caen refers to a council that decided the city should go to Bohemond. (RofC, 90) Councils were used to decide on leaders, maintain the common fund, and divvy up camp assignments and forts while static. It was a novel approach to a medieval military campaign.

The Semi-Princes

Within the leadership structure, there were two types of princes. There were major nobles like Godfrey and Raymond and minor princes like Tancred and Baldwin. These minor princes would play considerable roles in the later Crusader kingdoms. Tancred was Bohemund’s nephew and a constant companion of First Crusade accounts. He provides an example of the semi-princes within the leadership structure. Tancred and his like were minor magnates back west with an independent following who aspired to become equal with the higher-ranked princes or, if it went bad, back to a more dependent position. (Kostic, 20) This was the case with many young magnates across Western Europe. Success on the political and military front could make dukes out of knights and kings out of dukes. In three years of campaigning through the Holy Land, an aspiring noble could establish himself as an independent lord. (Kostic, 21) And that is precisely what Tancred and Baldwin had in mind.

Tancred was the son of Bohemund’s sister, Emma. His upbringing was that of any aspiring young man of the times. His life centered on military affairs and the spiritual realm. When Bohemund learned the First Crusade was on, he urged his nephew to join him as his second-in-command “as though a duke under a king.” (RofC, 24) Tancred agreed to join the other south Italian Normans, filling Bohemund’s role when absent. People flocked to Tancred’s banner and offered their allegiance as long as they received regular pay. Tancred used his wealthier supporters to pay for his less wealthy following. (Kostic, 22) The other young semi-prince was Baldwin of Bouillon, the younger brother of Eustace and Godfrey. Baldwin would one day become count of Edessa and king of Jerusalem, but for now, he fell under his brother. He also had a following like Tancred but served under Godfrey and captured cities in Cilicia under his older brother’s name. (Kostic, 23)

However, there was rivalry between the two commanders, akin to the fractured nature of their enemy. An example of the infighting that infected the leadership structure of both sides was the episode of Baldwin and Tancred outside Tarsus in late 1097. And this was replicated in the ranks of the nobler princes later in the campaign. Tarsus was located west of Antioch on the coastal route heading east. Baldwin and Tancred’s troops came to blows during their foraging campaign in September after a disagreement over who should control the town. Baldwin’s troops routed Tancred’s outside Tarsus and took control of the town. Around the 20th, three hundred Normans arrived outside the walls searching for Tancred. But Baldwin refused them access, and during the night, all of them were killed by Turkish forces prowling on the city outskirts. Baldwin’s men mutinied at the death of fellow Christians. But he survived the affair, and his fortunes eventually turned. (Kostic, 24)

Medieval Armies of the West

The medieval military of the late eleventh century consisted mainly of heavily armed cavalry known as “knights.” They were primarily recruited from the upper class of Western society. Knights are usually depicted fighting for wealth, honor, and advancement. (Backrach, 5) However, while the knights are often referred to, the infantry are poorly represented in the primary sources. They are simply referred to as numbers and mouths to feed. Since wealth sustained the Crusade, a long campaign was at the disadvantage of the non-wealthy. The infantry and poor of the army relied on either their lord, the Byzantines, or, later on, pillaging for food, water, and capital. To keep this group from starving during hard times, the leadership created a common fund to provide anything from funds to horses for down-on-their-luck knights. Close to the battle of Dorylaeum in 1097, Albert of Aachen refers to a common fund created by Bohemond and the other leaders to pool their food and supply resources. (AofA, 39)

The Aspect of Lordship that set Princes Apart

The most important thing a lord needed was revenue, be it raised in the preparation stages or from captured cities during the campaign. Control of tribute, paid out to followers, ensured a following. Arnulf of Chocques, Patriarch of Jerusalem, said this was the aspect of lordship that set princes apart. “You have promoted me from my humble position. You have made me famous, who was unknown. As if one of you, you bring about my sharing in tribute.” (Kostic, 25) However, the grueling length of the First Crusade created an atmosphere that tested the bonds of vassalage and obligation. Allegiance among knights shifted according to who could pay and support them. John Bell says money was a prerequisite for going on Crusade, whether you were a wealthy lord who needed to maintain his status and following, or a less affluent crusader. (Bell, 6)

Why is the Crusade Happening?

To understand why Western warriors needed to campaign through Asia Minor, it’s worth explaining the geo-political situation towards the end of the 11th century, which is messy. The Byzantine Empire, successors to the Romans, feared the growing power of the Muslims to the east. In the Byzantine mind, they were the Romans, and the Seljuqs didn’t disagree. The enclave ruled by Qilij Arslan was called the Seljuq Turks of Rum (Rome). Since the 7th century, the Byzantines had been fighting a rearguard action against the Seljuqs. After the Battle of Mantzikert in 1071, it was a slow and steady decline. The Seljuqs eventually pushed the Byzantines back across the Bosporus and maintained their front-line headquarters at Nicaea, forty miles southeast of Constantinople, a constant reminder of the threat. (Jandora, 101) The days of empire seemed long gone, but Alexios continued his diplomatic efforts to the spiritual leader of the West with the hope of finally rallying their warriors for a counteroffensive. Alexios is a good example of a great leader, at least for the interests of his empire. Pope Urban II granted his wish at Clermont in November 1095. He set the departure date as August 1096.

The Byzantines had no idea what they started, which may be testament to the corner they found themselves pinned in. They were no stranger to Frankish warriors, especially the Normans. Bohemond, under his father Robert, fought a war against Alexius in the 1080s with Norman intentions. (AK, 143) Anna Komnena was the daughter of Alexios and wrote a history dedicated to him but also to absolve him of any wrongdoing during the First Crusade. She has a grudging respect for the Franks, whom she refused to call anything but Kelts. Anna has an overall low opinion of Western warriors; she thinks they are good for one thing, cavalry charges.

The People’s Crusade

The People’s Crusade was the first group of Westerners to head east. They left Cologne around April 1096 but were not reflective of the proceeding Prince’s Crusade. Peter the Hermit led the effort and was as far from a military commander as possible. He motivated his army with fanaticism. As John Pryor quips, “Peter the Hermit was a student of the Bible, not De Re Militari.” (Pryor, 115) William of Tyre reports on an army split into two columns, one led by a nobleman known as Walter the Penniless, the other by Peter. (WofT, 104) The combined army consisted of about 15,000 – 20,000 men that covered 2400 kilometers in 104 days. (Pryor, 121) That’s about 23 kilometers a day, which is a quick pace compared to the follow-up formations. Peter’s columns were well on their way to Constantinople when the Pope’s departure in August came.

Market Transactions

Both columns encountered significant problems with the local population and the acquisition of supplies. Walter’s force is provided for at specific points early in the journey with markets from the Hungarian king, Coloman, but small elements of his force get separated and robbed. (WofT, 108) It’s a constant theme throughout the People’s Crusade. Small elements get into trouble with the locals; the local authorities retaliate, and conflict ensues. Lack of discipline led to their undoing. Markets were the primary way all Western forces sustained themselves, including the columns of the Peoples Crusade. It was a trait that harkened back to their pilgrim status. The markets probably consisted of a designated area where locals collected food and other necessities available for trade. (Bell, 27) In the chronicle accounts, the contingent leaders usually sent envoys ahead to a town to have a market set up in preparation for their arrival.

Peters’ column had the same issues as Walter’s until he made contact with Emperor Alexios. The peak of his march included having his baggage train destroyed by local Hungarians and his force dispersed until he entered official imperial territory. The People’s Crusade summed up: a series of disasters that ended with a spectacular battle and the massacre of its survivors by the Seljuqs. A very small remnant would, in fact, survive the ordeal and attach themselves to the Prince’s Crusade as they later marched through later that year. There is no evidence that Peter prepared for the task of feeding 15,000 – 20,000 people and their animals for 104 days. However, in Peter’s defense, it would have been a hard journey to plan for due to the distance and the lack of knowledge of the area they were traversing. (Pryor, 129) Most of the issues encountered on the People’s Crusade revolved around the lack of logistics, planning, discipline, and leadership.

The Princes Crusade

Anna Komnena described the approach of the Crusaders as preceded by a plague of locusts. “There was a first group, and then a second, followed by another after that, until all had made the crossing, and then they began their march across the mainland.” (AK, 276) She reports on Roman officers with orders to meet the Westerners at Dyrrachium, a significant port on the Adriatic coast, and supply them with adequate provisions gathered along the route. These representatives, known as kyriopalatios, were on the ground to interact with the locals, maintain good relations, and keep the foreigners supplied and off the raiding path. (Bell, 26) The officers attached interpreters with them to converse in Latin. They also had an alternate job, to keep a close eye on the Westerners as the Byzantines had plenty of experience with Norman adventurers.

Godfrey of Bouillon

Godfrey of Bouillon departed Regensburg eight months after the council of Clermont with foot soldiers and nobles from Belgium, Luxemburg, France, and the lower Rhine country. Godfrey sent envoys ahead to the authorities of the countries he marched through to ensure peaceful relations and the availability of markets in transit. During the journey, Godfrey and his followers purchased bread, wine, grain, barley, farm animals, and fowl from local markets and independent peasants. Pillage was reported in the chronicle accounts but not on the scale of the People’s Crusade. Godfrey’s column marched southeast through Hungary, then south into imperial territory, where they were met at the border by an imperial envoy who gave them permission to trade and purchase supplies locally, subject to good behavior. (Pryor, 129) Godfrey’s army was the first group to cross the Bosporus. He began his march in August and arrived outside Constantinople on December 23.

Bohemond of Taranto

The route to Constantinople was familiar to Bohemond and the south Italian Norman group. His cadre landed along the east coast of the Adriatic and concentrated on the town of Avlona, south of Dyrrachium. Bohemond didn’t get on the Via Egnetia, the south leg of the pilgrim route, until he reached the town of Vodena. He fought for control of this place not ten years prior, so he may have had business, other than crusading, to attend to. (France, 103) The Gesta Francorum reports on Bohemond’s force resupplying in Bulgaria with plenty of grain, wine, and other food through local markets. They arrived at Castoria and wanted to purchase provisions, but the locals were leery of them, probably for good reason. So the Crusaders turned to tactical acquisition (theft) to grab everything they needed, including cattle, horses, and donkeys. (Anony., 15) As he approached the capital, Bohemond sent an embassy to Constantinople to assure the emperor of his good intentions. Alexios sent a curopalate, another type of imperial envoy, to guide Bohemond’s force the rest of the way to Constantinople. This envoy provided all the supplies the army required for its final destination. Bohemund turned the army over to his second in command, Tancred, and went ahead to Constantinople to meet with the emperor, arriving at the beginning of April. (France, 104) Bohemond’s force journeyed 178 days, averaging just over five kilometers per day. (France, 107)

Raymond of Toulouse

Raymond IV was the wealthiest of the Frankish nobles. He was the eldest at fifty-five and led the largest group of Provencal’s from southern France. He departed from Le Puy in mid-December 1096. He also chose the longest route, and though he decided to march through the mountains of northern Italy and Bulgaria in the dead of winter, he came out relatively unscathed, a testament to careful preparations. Raymond of Aguilers was a chaplain in his army and reported problems later in their march. For three weeks, they desperately foraged and found nothing. The route had been ravaged by previous formations, particularly Bohemond’s. (France, 104) Raymond’s force covered almost 3,100 kilometers in a seven-month journey, arriving at Constantinople on April 21, 1097. Raymond of Aguilers says his leader chose the landlocked route because the cost of ferrying troops across the Adriatic would have been astronomical. Raymond’s army marched almost the same distance as the Italian Normans but with a much bigger army, averaging over eleven kilometers a day. (France, 108)

Robert of Normandy, Robert of Flanders, and Stephen of Blois

Robert of Normandy, Robert of Flanders, Stephen of Blois, and the north French contingent traveled south through Italy to Bari on the Adriatic. Robert of Flanders crossed while Robert of Normandy and Stephen stayed behind due to the onset of winter. They departed in early April 1097 and leisurely marched to Constantinople, arriving in mid-May, well into the siege of Nicaea. Their journey was not without its pitfalls. In Bari harbor, a ship capsized, drowning four hundred people and causing many to turn back. When crossing the Demon River, many of the foot soldiers drowned. (France, 103) The North French contingent covered about 920 kilometers in thirty-six days, averaging twenty-five kilometers a day. (France, 107)

Crossing the Bosporos

Anna Komnena says Bohemund and the rest of the nobles met on the coast of Marmara, the gap between the Black Sea and Med, and crossed to Kibotos, where they met Godfrey and waited for Raymond. She says their numbers were too large to sustain supplies, so they split into two groups, one pressing ahead through Bithynia and Nikomedia for the first stronghold of Nicaea, the other consolidating slow arrivals. (AK, 297) The Crusaders were completely reliant on the Byzantines for logistical support. They didn’t have ships, so they relied on Byzantine sailors to ferry them across the Bosporus. And Byzantine sailors didn’t have to rush the job by transporting all the troops in one big go. The individual contingents arrived at Constantinople and were transported piecemeal to the Anatolian side. Godfrey crossed in February 1097, probably with Robert of Flanders. The Italian Normans crossed the Bosporus in April, while the southern French crossed in early May, followed by the remaining north French later that month. (Bell, 57)

On the Anatolian side of the Bosporus, supplies were obtained the same way they did on the route to Constantinople, by markets and access to Byzantine logistics. Fulcher of Chartres reports on the Crusaders buying food transported on ships by order of the emperor. (FofC, 333) Albert of Aachen is more specific, he says the emperor “granted a most generous facility for buying and selling everywhere in his kingdom. On imperial orders, sailing merchants were striving to race across the sea with ships full of rations, corn, meat, wine and barley, and oil.” The Crusaders used the markets opened at Civetot to buy a variety of provisions in addition to Alberts’s list. (AofA, 110)

Once Alexios got the Franks across the strait, he appointed Tatikios as the Byzantine liaison with two thousand additional soldiers. At the time of the siege of Nicaea, Tatikios was ductor Christiani excercitus, a top Byzantine military leader. (Kostick, 13) Once the Crusaders were consolidated in Bithynia, their first objective was the city of Nicaea. There was an existing road network that led to these cities. But the roads of Anatolia, under Seljuq control for years, were a shadow of their former self. The most recognizable achievement of Roman armies in the first century BC to the late second century AD was the construction of a network of major arterial roads through the interior of Anatolia. These roads were pivotal in funneling men and materials from the inner provinces to the frontier and connecting the provinces to the political center, Constantinople. (Pryor, 135)

Road Network of Anatolia

Unlike the pilgrimage roads, the roads in Anatolia probably suffered from the lack of attention brought on by the chaos and continuous warfare of the Muslim conquests. John France said the pilgrimage routes were used well into the First Crusade. (France, 100) From the sixth through ninth century, maintenance on Byzantine roads declined and became a local concern rather than an imperial one. The change was seen in the type of vehicles used in the region. Pack animals replaced wheeled carts and wagons, which steadily led to the narrowing of many roads outside Constantinople’s immediate environs. (Pryor, 136) Under optimal conditions, a two-wheel mule-drawn cart could cover up to thirty kilometers per day, while an ox-drawn four-wheeled vehicle could cover between ten and twenty-four kilometers per day. (Haldon, 21)

Godfrey was the first across the Bosporus and didn’t waste time. He ordered an advance guard of three thousand men to use axes and swords to cut and widen the road south to Nicaea. (Anony., 15) That probably means the old Roman roads were overgrown. Godfrey, Tancred, and Robert of Flanders, along with the remnant of the People’s Crusade (there was a small group of survivors), marched along the Gulf of Nicomedia, through Rufinel, to approach Nicaea from the north. They arrived around May 6, 1097, building a camp and developing siege lines. (France, 122) The Crusaders built lines of vallation of the city and contravallation of the camp to protect the army and non-combatants from a relief force or raiders. The author of the Gesta Francorum says the Crusaders were already short of supplies when they reached Nicaea, but Bohemund arrived within the week with a baggage train filled with the necessities. (Anony., 34)

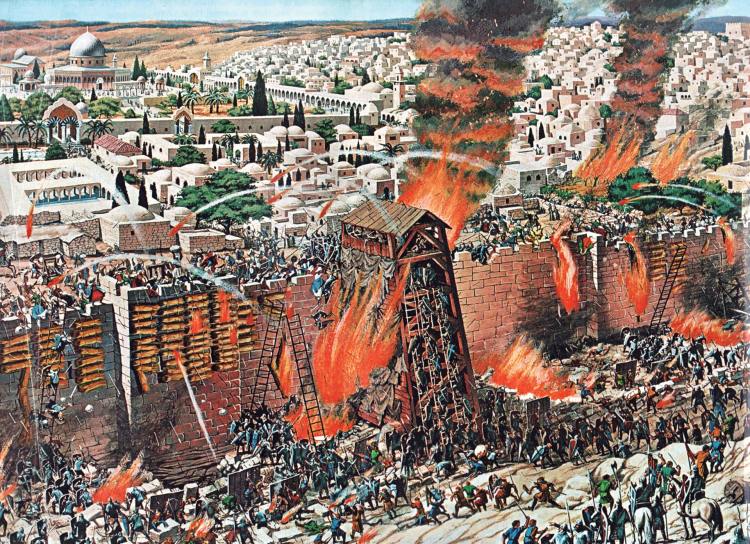

Siege of Nicaea

On May 14, the Crusaders officially invest the city, utilizing wooden siege engines and towers to breach the walls. Fulcher of Chartres says the leaders ordered their men to build scrofae, petrariae, and tormenta. Scrofae was a shed that protected the sappers digging, while petrariae, and tormenta launched stones. (FofC, 114) After two days of hard fighting, they began digging underneath the walls. (Anony., 36) The Crusaders excelled at this type of activity. Starvation was the preferred method of warfare during this age. The siege was that and became their preferred tactic. Victory came from blockading the defenders behind their walls until they ran out of provisions or surrendered. But the offensive army was always at risk of famine and disease, which we will see later at Antioch. The threat was made worse when the defending army used scorched earth tactics, like the Seljuqs, after each defeat, denying the surrounding countryside of anything the Crusaders could use. (O’Dell, 46)

Muslim Relief Force

While the Crusaders laid siege to Nicaea, the Muslim forces gathered a relief effort to the east. According to Ibn al-Qalanisi, the leader of the Seljuqs, Qilij Arslan, received numerous reports on the approach of the Franks. After confirming them, Arslan “set about collecting forces, raising levies, and carrying out the obligations of Holy War.” He also summoned additional support from the Turkmen and the askar of his brother. Arslan’s relief force numbered around 10,000, and they approached Nicaea with the impression they would cut through the Westerners with as much ease as they did the People’s Crusade. Qalanisi recalled the Battle of Nicaea with dread. (Qalanisi, 46)

The Gesta Francorum reports on how brutal the battle was, with the end consisting of decapitated heads hurled over the walls to a beaten enemy. He describes how Raymond and Adhemar strategized to take down the towers in front of their camp. The Crusaders chose picked men to dig at the base of the towers with an arbalest and archers providing overwatch. They moved in the evening, digging to the wall’s foundations, piling up wood, and setting it alight. The tower came crashing down that night, but it was far too dark to fight, and the defenders restored their defenses by daylight. (Anony., 37) This scenario was replayed consistently throughout the Crusade, huge inroads denied.

Boats from Civetot

While the Crusaders continued their effort, the besieged inside Nicaea, already well supplied, received still more through the lake, flanking the city to the west. From this vulnerable point, the Seljuqs occasionally launched boats to harass the siege lines. The Crusaders couldn’t proceed without plugging the gap, so they appealed to Emperor Alexios for boats from the port of Civetot. This was no simple maneuver. The emperor made the ships available, but the Crusaders had to drag them by oxen over mountains and through a forest to the west side of the lake. He also sent along Turcopole warriors (Light cavalry and mounted archers of mixed Greek and Turkish parentage) to escort the column and fight on the boats. (Anony., 38) But the end of Nicaea was anticlimactic.

On June 19, the Muslim commander surrendered directly to Byzantine authorities with extremely favorable terms. Alexios used his unique brand of diplomacy to convince the garrison to surrender directly to his officials, bypassing the Crusaders and a guaranteed brutal sacking. The end of the siege was the first of many slights against the Crusaders. They saw Alexios’s move as depriving them of substantial plunder promised by the rules of war, a sort of breach of contract. Alexios tried to pacify them with expensive gifts to the leaders and a donative of copper coin for the rank and file. But the damage was done.

Logistics at the Siege of Nicaea

The speed at which the Crusaders took Nicaea is a testament to the logistical infrastructure provided by the Byzantines. During the siege, Fulcher of Chartres reports on the Crusaders resupplying food stocks from ships sent with the emperor’s consent. He describes crusader forces working at peak efficiency. They are not stricken with hunger or thirst and have plenty of materials to construct proper siege equipment. Logistics were so good the Crusaders could get imperial ships from the port of Civetot and haul them overland with relative ease and safety. That’s logistics at its best. The Byzantine war machine was behind them completely and victory at Nicaea was practically inevitable. (FofC, 115)

Following the siege, there is a notable absence of information regarding the army’s logistics. There’s no detail on the refurbishment of equipment, the preparation of horses for the long march, or food gathering. The only logistical aspect mentioned is that Alexios provides food for the impoverished. (Pryor, 58) The Crusaders spent seven weeks outside of Nicaea, likely scouring the landscape for plunder and supplies, as they needed adequate provisions for the next leg of their journey. Imperial officials still offered regular logistical assistance, utilizing both land-based and naval assets, while private merchants, licensed by the Byzantine administration, had the authority to issue the necessary documents to buy and sell. (Pryor, 59)

Oaths to the Emperor

From Nicaea to Antioch, the Crusaders fell under the auspices of the Byzantines, regardless of hurt feelings. Not only did they make oaths to the emperor, but they marched at his pleasure as he was responsible for keeping the flow of supplies running. Traversing Anatolia would be very different from previous stages of the Crusade. The terrain was ever-changing. Anatolia, modern-day Turkiye, is a rough landscape, encompassing an immense semiarid plateau containing plains broken by peaks and troughs. (Haldon, 123) To the south, two mountain ranges barred entry into Syria and the Holy Land. (Bell, 67) Food was available for the grab in the fertile lands farther to the south, closer to the littorals, but the army had to cross uneven and desolate terrain to reach this more abundant area.

The Road to Antioch

The army stepped off on June 26, following the Roman road south for thirty to thirty-five kilometers. Stepping off in June meant the Crusaders marched to Antioch during the hottest part of summer. That was reflected in the chronicle accounts. In July, the Anatolian plateau records a daily maximum of eighty-two degrees Fahrenheit and a minimum of fifty-nine degrees Fahrenheit. (France, 137) The Franks were known for the amount of equipment they carried, and it quickly became a hindrance to them in this hot, foreign landscape. Water was their most precious possession. Albert of Aachen reports five hundred deaths from lack of water. (AofA, 156) The Gesta Francorum and Fulcher confirm great suffering in the army around this time. (GF, 126)

Wagons and Grain

John Pryor suggests they likely departed with around six hundred wagons filled with grain and other supplies intended to last three days. And that’s not including the vehicles carrying equipment and fodder for the animals. They probably established their camp on the left bank of the Sangarios River, close to the old Byzantine aplekton, or fortified camp, at Malagina. (Pryor, 60) Most of the forces remained here for two days, as the Crusaders needed to collect at least a hundred metric tons of grain, strictly for human consumption, to sustain their column forward. Alexios’s officials implemented the traditional Byzantine method of resupplying the army during the journey to Dorylaeum. The imperial supply depots, which were so instrumental in keeping Byzantine armies fed and equipped earlier in the century, were being re-established in the wake of the invasion. With about 2,000 wagons, 50,000 men, and 10,000 horses, the line of march extended almost 40 kilometers. (Pryor, 57)

The Crossroad of Dorylaeum

The long column marched for three days and split into two divisions, with Bohemund leading the vanguard and Raymond the rearguard. This is the first sign of the Crusaders splitting up for logistical reasons. On July 1, the Seljuqs ambushed Bohemund’s column, leading to the vicious battle of Dorylaeum. The author of the Gesta Francorum estimated the opposing force to be 360,000 Persians, which is an exaggeration. (GF, 128) These guys weren’t experts in estimating numbers, they were warriors; he means a very large number of mounted Seljuqs. At the height of the battle, Bohemund’s force reformed and fortified a camp around their supply train. Fulcher of Chartres says the rearguard removed their pack saddles, or clitellae, to join the fight. (Bell, 71) The Crusaders counterattacked when reinforcements arrived, taking the Seljuq encampment, which included a baggage train hauled by camels, an animal the Crusaders had little experience with. They took two days, July 2 and 3, to resupply and rest. The booty taken from the Seljuq camp was apparently substantial and probably sold or traded at ad-hoc markets for additional supplies and funds. (Pryor, 61)

Dorylaeum was an important location. It was formerly a Roman waystation and nexus to the road system spreading out into Anatolia. Supply trains could flow through this node from Nicaea and the port of Civitot and follow them further inland to the east. They could resupply at this important node and choose the best route toward Antioch. Dorylaeum also provided a secure location to fall back on if the worst happened. The Crusaders could travel on the ‘Pilgrim’s Road’ through the Cilician Gates, a 350-kilometer route, or they could take the northern passage through the Amanus Mountains via Caesarea, a 630-kilometer route. (O’Dell, 53) But one thing was for sure. They couldn’t travel as one long, drawn-out force through the rest of the country. The region couldn’t sustain it, and traveling as one large formation left them vulnerable to attack. To make matters worse, after each battle, the Seljuqs destroyed everything in their path to Iconium, 150 miles east. There was a method to the madness. The Gesta Francorum says the Turks destroyed fields, animals, and shelters, anything they couldn’t take and might sustain the Crusaders on their way to Antioch. (Bell, 75) Anything to hinder their progress.

The Crusaders stayed at Dorylaeum for two days. They probably went from Dorylaeum to Philomelium, approximately 130 miles east, where the land and local population were supposedly easier going. Though this region was under Seljuq control for years since the Byzantine fall, most of the population was still primarily Christian and not averse to a Byzantine or Frankish takeover. The next leg of the journey would have taken them to Iconium, another 20 miles, a location which may have provided additional provisions. But with the Seljuqs using scorched earth tactics to effect, the Crusaders grew concerned about running out of the essentials. (85)

Food Intake for 50,000 men

After the battle of Dorylaeum, the Crusaders were presented with a new hard reality. They had many men to feed; the landscape was desolate, and their normal procedure for obtaining food through markets was nearing its end. According to the minimalist model presented by John Pryor, the Crusaders needed to provide sustenance for approximately 50,000 individuals. The estimated caloric intake was around 50,000 kilograms, or 50 metric tons, of milled wheat daily. (Pryor, 54) Transporting the food posed another challenge. They required about a hundred horse or mule-drawn carts or wagons, each with a maximum load capacity of approximately five hundred to six hundred kilograms. Pryor said the Crusaders had roughly five thousand cavalry, with each rider typically managing two or three additional horses: typically, a warhorse (destrier), fast horse (courser), and small all-purpose horse (rouncey). These extra mounts may have carried extra supplies.

Local Populations of Anatolia post-Dorylaeum

The geographic and population patterns of the next leg of the march favored the Crusaders. They marched through Philomelium and the fertile Konya Basin, which centered on Iconium. Then, they traveled through the abundant, populated region on the north side of the Taurus Mountains. (Haldon, 113) From Philomelium, the villages they encountered were generally within fifty miles of each other. The proximity of these towns, where the inhabitants generally aided the army, made for a peaceful leg of the journey. (Bell, 77) Raymond of Aguilers described this part of the crossing as relatively easygoing. (RofA, 133)

One of the cultural groups the Crusaders encountered in this region was the Armenians. Cilicia was the old border region between the Byzantine Empire and Syria, but since the Turkish conquests, Armenian lords began vying for control of the area. (Bell, 88) The Gesta Francorum refers to them as allies. They provided supplies for his contingent and opened their towns to them. (GF, 49) Armen Ovhanesian describes a beneficial relationship between the Crusaders and Armenians, “when in past times the Christian princes and armies went forth to recover the Holy Land, no nation, no people came to their aid more speedily and with more enthusiasm than Armenians, giving them assistance in men, horses, food, supplies, and counsel; with all their might and with the greatest bravery and fidelity they helped the Christians in those holy wars.” (Ovhanesian, 1) The status is reported alternatively by other sources at different times during the campaign; for example, Albert of Aachen accuses a group of Syrians and Armenians of cheating the Westerners out of money when food becomes scarce at Antioch in 1097. (AofA, 183)

Looting in the Chronicle Accounts

Gregory Bell points out that as the Crusaders traveled through Anatolia, the number of references to looting significantly dropped compared to their trips through Hungary and the Byzantine Empire. There were seventeen references to looting in the chronicle accounts as the crusade armies passed through Byzantine and Hungarian land. However, in the same chronicles, Gesta Francorum, Raymond of Aguilers, Fulcher of Chartres, and Peter Tudebode mentioned the occurrence of looting only seven times between Nicaea and Antioch. (Bell, 77) The evidence may suggest the last half of the march through Anatolia was relatively easygoing, at least by 11th-century standards.

Raiding the Countryside

One solution to feeding so many people was to send small strike teams of knights into the countryside to raid and live off the countryside. In September 1097, Tancred and Baldwin were sent on a mission through the Cilician Gates to conquer the coastal ports northwest and the towns north and east of Antioch, including Tarsus and Edessa. Ralph of Caen says Tancred had around a hundred knights and two hundred archers, while Baldwin commanded five hundred knights and two thousand infantry. (RofC, 57) Their force was miniature compared to the main body. They covered around 220 miles, while the main body took the longer route, about 400 miles, staying north of the Taurus mountains along a road that passed through majority Armenian Christian towns. (Bell, 91)

Tancred and Baldwin led smaller, faster detachments that could work dynamically. They could take and control a region without worrying about feeding 50,000 mouths. The leadership decided to send the main army through territory where they could take their time, and there was a better chance of obtaining food without conflict. (Bell, 86) As the main body crossed the mountains and entered the plains north of Antioch, the leaders began to branch out with their own small detachments, similar to Tancred and Baldwin, to take and hold ground in the north. (Bell, 91) They arrived outside the mighty walls of Antioch in October 1097. (Anony., 48)

Foraging Center

These detached groups established “foraging centers,” or satellite bases, throughout the region to act as supply depots for the main camp. (Bell, 85) At Antioch, maritime operations began in earnest as fleets of ships, Byzantine and Frankish, set out to conquer the port towns around Antioch and supplement the main body. While the Crusaders crossed the Taurus mountains, two fleets had already begun to establish an allied presence on the coast. (Bell, 92) Over the next two years, an additional four fleets appeared in the eastern Mediterranean with direct support for the Crusader effort. These included an English or Byzantine fleet, a Genoese fleet, and a fleet of Flemish, Frisian, and Danish sailors fighting for the pirate Guinemer of Bouillon. (Bell, 93)

Supply via Littoral Ports

John Pryor talks about an English fleet that participated in the early siege of Antioch and helped take the port of St. Symeon, the most important supply node for the Crusader effort thus far. (Bell, 95) John France says they arrived on March 4, 1098, and enabled the Crusaders to tighten the screws on the siege. (France, 254) The timing of this northern fleet speaks to the preparations made before the campaign had even started. The evidence of these fleets is confused in the primary sources, but their presence is nonetheless a constant theme. Once the Crusaders established regional ports, they would have access to provisions from across the sea, possibly Cyprus, a Byzantine possession at the time. Byzantine ships could sail from Constantinople, around Anatolia, and deliver provisions to the Cypriots, who could then distribute the supplies to the numerous ports around Antioch, principally St. Symeon. (Bell, 105)

Feeding the Army at Antioch

Antioch marked a new challenge for the Crusaders. Instead of relying on markets and the next town, they would have to feed a vast, static army. (Bell, 83) Antioch was a unique city, the gem of the old Roman Mideast. It was sheltered by a mountain range and layered with imposing walls and towers. The Orontes River flowed across the west face of the city all the way to the Mediterranean. Fulcher’s description of the life-giving river highlights its importance,

“Because the Orontes River flows into the sea at that point, ships filled with goods from distant lands are brought up its channel as far as Antioch. Thus, supplied with goods by sea and land, the city abounds with wealth of all kinds.” (Fulcher of Chartres, 146)

As the Crusaders approached the walls of Antioch, they built camps at the main gates and prepared for a long siege. They pillaged the local countryside for supplies and established a line of communications from their main camp on the west side of the city to the ports under their control, primarily St. Symeon to the south. This line was contested throughout the siege. Peter Tudebode says, “Soon we were ensconced in the neighborhood, where we found vineyards everywhere, pits filled with grain, apple trees heavy with fruit for tasty eating, as well as many other healthy foods.” (DRM Peter) But the bounty wouldn’t last long.

The Port of St. Symeon

The importance of St. Symeon was obvious from the beginning of the siege. To keep their supply lines open, the Crusaders built counter-fortifications around Antioch and stationed a large garrison at the port. They supplemented their food stocks with booty after multiple battles with enemy relief columns. The Gesta Francorum describes a vicious battle at the Iron Bridge where they defeated the Turks and acquired a bunch of plunder, including horses, camels, mules, and donkeys laden with grain and wine. (Anony., 51) The siege developed into a tit-for-tat as the garrison of Antioch sallied out, and the Crusaders fought them off, all the while counter-attacking Muslim relief forces from Syria and Iraq and continually maneuvering to further strangle the city.

A Relief Expedition into Syria

Before Christmas 1097, the Crusaders run into serious supply issues. All foodstuffs, including grain, are low. They hold a council and decide to send a foraging expedition into Syria to gather provisions while the other half protects the camp and mans the siege lines. Fulcher reports a complete scarcity of food, where ordinary men don’t have the capital to buy anything. (FofC, 147) The Gesta Francorum says the expedition left on a Monday with twenty thousand men. Another battle occurs at the end of December, where it again looks like the Crusaders will be defeated, and they again come out on top. The increase in supply is summed up the Norman way, “Our men took their horses and much other loot.” (Anony., 55)

Foraging Center in Action

The description of Peter Bartholomew, a commoner in Raymond of Toulouse’s camp, shows how a foraging center at Antioch worked. Peter and his group rotated from one camp to the next, using up a small amount of food and transporting the rest to Antioch on pack mules. Then, they set out for another satellite camp. John Bell points out that lords like Baldwin and Bohemond ran these satellite territories, but the provisions were available to all, regardless of the overlord. (Bell, 124)

The Counter-Fortifications of Antioch

In March, the leaders built more counter-fortifications at pressure points along Antioch’s main gates. It’s interesting that the building of these fortifications coincides with the arrival of allied fleets in the eastern Med. The Crusaders elected Tancred to take control of the counterfort outside the St. George gate in the southern wall, offering him four hundred silver marks to cordon off the city to the south and east. Raymond of Aguiler reports on Armenians and Syrians who tried to bring supplies into the city through the mountains to the east, but Tancred was able to use his position at the counterfort to capture most of them along with, “all that they had brought, namely grain, wine, barley, oil, and other things of this sort.” (RofA, 132) This may also represent an alternate position of the allied Armenians; they probably fought for both sides and in between. On June 3, 1098, the Crusaders took the city in a ruse concocted by Bohemund. But there was no time for celebration. The atabeg of Mosul, Kerbogha, was already on his way with a massive Muslim relief force.

The Reverse Siege

On the third day after the capture of the city, the Muslim advance guard appeared before the walls and set up camp outside the Iron Bridge. This initial force was led by Curbaram, who was answering a request for help from the emir of Antioch, then under siege by the Crusaders. His army joined with the emir of Jerusalem and the king of Damascus. (Maalouf, 73) The Muslims now had the Crusaders holed up in a city that just emerged from a brutal eight-month siege. They had little time to prepare before Kerbogha’s arrival and food stocks within the city were spent. And the reverse was devastating to crusader morale. The author of the Gesta Francorum says many died of hunger, while others survived on the dried skins of horses and camels. He describes people selling these types of items in ad hoc markets at absurd prices; in one account, a hen cost eight or nine solidi. This example shows just how embedded the logistical practice of buying food at markets was even during a severe crisis. (Bell, 141) Around this time, the Crusaders experienced a number of important desertions, including Stephen of Blois. (Stephen was operating outside of Antioch when he saw the size of Kerbogha’s army. He deserts and retreats west, where he encounters Alexios, who is on his way to Antioch with a good-sized Byzantine relief force. Stephen convinces Alexios to turn his army back to Constantinople with the threat of an additional phantom Muslim relief force preparing to strike from somewhere else in the north)

Naval Presence in the Mediterranean

The naval power of the Byzantines and the West was an essential component to the crusader’s success. During the First Crusade, particularly at the siege of Antioch, the Byzantine navy and ships from the west began concentrating in the eastern Mediterranean. (Pryor, 15) Although the reinforcements were few, the skills they brought were very important to the land army. (France, 211) A Genoese fleet of thirteen ships, twelve galleys, and one hybrid-oared ship, filled with armed men and equipment, left for the east on July 15, 1097. They arrived at the port of St. Symeon on November 17, 1097. A few days later, the leaders built a fortress on Malregard Mountain. Bruno of Lucca arrived at St. Symeon on March 4, 1098, and the next day, the leaders built a fort outside the Bridge Gate, known as the Mahommeries Tower. While the siege of Jerusalem was in its early stages, a fleet of six ships put into Jaffa, including two Genoese vessels. But while the Byzantines and West built up their naval presence in the Mediterranean, so were the Fatimids. In 1099, a Fatimid fleet threatened to attack that same Western fleet at Jaffa. The sailors grounded their ships and burned what they couldn’t bring with them. They marched with the ground element to Jerusalem, carrying useful materials with them. Now part of the land army, William Ricau fell in as an engineer who built a siege tower and other machines for Raymond’s contingent. (France, 212)

A Secure Base of Operations

In June 1098, the Crusaders defeated the Muslim relief force led by Kerbogha at the battle of Antioch. (Anony., 73) The battle is important from a leadership standpoint because Bohemond was elected through a council for sole command. Antioch became the base of operations and a secure food source, primarily through ports like St. Symeon. (Bell, 146) Possession of Antioch also ensured the Crusaders a position to retreat to if things went bad proceeding south. Since Bohemund led the Crusaders to victory in the battle and siege, the leaders chose him to take control of the city and consolidate their gains. He would not join the army heading south. The leaders debated in council whether to take the coastal route south or travel overland via Damascus. (Bell, 152) If they went north, the link to their supply base might be cut; the same could be said about the coastal route south, but at least the navy could shadow them from the east and supply them down to Jaffa. (Bell, 150) The coastal route won out.

The March to Jerusalem

They waited for spring and the collection of the local harvest to begin the march toward their ultimate objective, Jerusalem. The Gesta Francorum says, “Duke Godfrey, Count Raymond, and Robert of Normandy, as well as the Count of Flanders, saw that the harvest was quickly being collected, as we had been eating new beans in mid-March and cereal grains in mid-April.” (Bell, 163) The army set off south from Kafartab to Shaizar, where they received the envoys of local Muslim dynasts, which granted safe passage to the Crusaders and the right to buy goods, including vitally needed horses. (France, 315) During my research, this was where the Muslim warrior Usama Ibn Munqidh, then not born, but his uncle and father interacted and came to terms with this first group of crusaders. War was part and parcel of the ‘terms’ laid out between the two sides, as attested by Munqidhs life in the saddle confronting the infidel Franks. The First Crusade columns, however, cut through this region with relative ease, with the exception of Ma’arra and Akkar. Albert of Aachen said the emir of Tripoli came to terms with the Crusaders and sent a sort of liaison officer to accompany the army and lead them through the dangerously narrow passages of the coastal road. (France, 328)

The Pace Quickens

The Army left Ma’arra on January 13, 1099, and traveled 160 kilometers to Akkar, arriving on February 14. The trip took about thirty-two days, with the army averaging about five kilometers. However, they rested at Shaizar for five days and spent fifteen at Crac des Chevalier, so their average was closer to thirteen kilometers. (France, 330) The rate of march accelerated as the Crusaders got closer to their objective. For two days, between Tripoli and Beirut, they made forty kilometers a day. But time was against them. From their point of view, the rest of the campaign was dominated by the need for haste, and the speed of the march reflected that reality. One reason for the haste was that it was abundantly clear that the Crusaders and Fatimids were about to come to blows. John France talks about negotiations with the Fatimids before the march south, possibly as early as pre-Antioch. But once the Crusaders crossed the Orontes River heading south, the Fatimids knew war was on, kind of like the First Crusades Rubicon. However, it would take a significant amount of time for the Fatimids to mobilize an appropriate army to confront the Crusaders.

Jaffa-Ramla lifeline

Leadership towards the end of the campaign revolved around Raymond and Godfrey as Bohemond stayed in Antioch to consolidate crusader gains. Their force passed through Tripoli, Beirut, Tyre, Acre, Haifa, and Caesarea, rarely stopping for a significant period of time. They picked up essential supplies on the way via foraging and looting. All lands that hadn’t come to terms, the Crusaders deemed hostile. (Bell, 165) They captured Jaffa and Ramla, the lifeline leading to Jerusalem. The Gesta Francorum says the Crusaders left detachments of knights and infantry to man the strong points in Jaffa and Ramla. (Anony., 101) As the vanguard crossed over the Judaean hills, it must have dawned on them that this would be different than previous stages. They no longer had Byzantine support and were entirely responsible for sustaining themselves. Enemy territory lay between the army at Jerusalem and Antioch, their base of operations four hundred miles to the north. (Bell, 166) The Crusaders had to depend on their immediate environs. They had to pillage what they could and keep their lines of communication open with Jaffa, which the Fatimids continued to pick at with small raids.

Army Size by the Siege of Jerusalem

Gaston of Bearn and Tancred were sent ahead to screen the main body and raid. (France, 335) They entered the Promised Land in the dead of summer. According to Raymond of Aguilers, the army approaching Jerusalem on July 7, 1099, numbered about twelve hundred to thirteen hundred knights and twelve thousand infantry. (France, 330) Even accounting for the numbers deducted for garrison duty at Antioch and other strongholds, including the Ramla-Jaffa lifeline, this was a significantly chiseled force compared to the grand army that departed Nicaea in 1097.

Water and Wood

As with all sieges of Jerusalem from the beginning of time, water became their most pressing need. Raymond of Aguilers describes the Crusaders as unbearably thirsty and says the heat, dust, and wind made it worse. (France, 167) They tried transporting water from Ramla using animal skins as bladders, but by the time they got to camp, it was just sludge. Raymond says they had no choice but to force it down. But at least the Crusaders had access to large stockpiles of food. On June 17, ships arrived at Jaffa with materials for siege equipment (William Ricau’s boat ride). The shipment was a godsend because the region was also bereft of wood. The author of the Gesta Francorum complains that they would have taken the city on the first day if they had the wood to build siege ladders. (Anony., 101) With the wood, materials, and engineers the fleet brought in, the Crusaders could build appropriate siege equipment to make quick work of the defenses. They don’t walk into the Holy City, but after several false starts, they storm into Jerusalem on July 15, 1099.

Some Conclusions

The Franks began this brutal campaign completely dependent on the Byzantine emperor for food, water, counsel, and supplies; anything to sustain an army in the field. Not only did they need sustenance from him, but the Western leaders also gave oaths to Alexios. This quasi-feudal arrangement required them to return any prior imperial territory back to the Byzantines. However, that policy changed after the siege of Antioch. When Stephen of Blois deserted the Crusaders at Antioch, he encountered Alexios and convinced him to also turn back his relief army. The Crusaders considered this a betrayal, and the oaths of the various leaders to Alexios became null and void except for a few diehards, like Raymond of Toulouse. Following the Battle of Dorylaeum, Alexios and the Byzantines focused more on re-establishing imperial control over the territory already cleared by Crusader forces and less on assisting them in reaching their objective.

The Armed Pilgrims of the First Crusade

From Antioch to Jerusalem, the Crusaders relied on their prior war experience and the adventurous spirit of the sailors from England, Genoa, Venice, and Pisa, who made pivotal port calls at St. Symeon and Jaffa to keep the flow of men and materials constant. I have more questions than answers after this project. I would attribute the Crusaders success to their ability to adapt to unexpected challenges, a skill likely rooted in their past experience and their identity as armed pilgrims journeying to the Holy Land. When Pope Urban II issued his call to arms in November 1095, he may not have realized that he was, in effect, influencing logistical policy. Like traditional pilgrims, the Crusaders acquired supplies along their journey through bartering and market transactions, resorting to violence when necessary. Pope Urban’s notion of the armed pilgrimage fostered a collective identity among the participants, empowering them to endure unimaginable pain and suffering.

Bibliography

(RofC) Bachrach, Bernard. The Gesta Tancredi of Ralph of Caen A History of the Normans on the First Crusade. Translated by Bernard Bachrach and David Bachrach. Ashgate, 2005.

Backrach, Bernard S. “Medieval Siege Warfare: A Reconnaissance.” The Journal of Military History 58, no. 1 (1994). https://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.lib.uwf.edu/stable/2944182.

Bell, Gregory D. Logistics of the First Crusade: Acquiring Supplies amid Chaos. 1st ed. Blue Ridge Summit: Lexington Books, 2019.

(Anony.) Dass, Nirmal. The Deeds of the Franks and Other Jerusalem-Bound Pilgrims: The Earliest Chronicle of the First Crusade. Translated by Nirmal Dass. 1st ed. Blue Ridge Summit: Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 2011.

Decker, Michael J. The Byzantine Art of War. Pennsylvania: Westholme Publishing, 2013.

(AofA) Edgington, Susan B. Albert of Aachen: Historia Ierosolimitana, History of the Journey to Jerusalem. Translated by Susan Edgington. Clarendon Press, 2007.

France, John. Victory in the East: A military history of the First Crusade. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

Haldon, John, Neil Roberts, Adam Izdebski, Dominik Fleitmann, Michael McCormick, Marica Cassis, Owen Doonan, et al. “The Climate and Environment of Byzantine Anatolia: Integrating Science, History, and Archaeology.” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History 45, no. 2 (2014): 113–61. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43829598.

Haldon, John, Vince Gaffney, Georgios Theodoropoulos. “Marching across Anatolia: Medieval Logistics and Modeling the Mantzikert Campaign.” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 65, (2011): 209-235. https://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.lib.uwf.edu/stable/41933710.

Ibn Al-Qalanisi. The Damascus Chronicle of the Crusades. Translated by H.A.R. Gibb. New York: Dover Publication, Inc., 2002.

Jandora, J. W. “Developments in Islamic Warfare: The Early Conquests.” Studia Islamica, no. 64 (1986): 101–13. https://doi.org/10.2307/1596048.

Kaldellis, Anthony. The New Roman Empire A History of Byzantium. New York: Oxford University Press, 2024.

(AK) Komnene, Anna. The Alexiad. Translated by E.R.A Sewter. London: Penguin Classics, 2009.

Kostick, Conor. “The Leadership of the First Crusade.” In The Social Structure of the First Crusade. Brill, 2008. https://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.lib.uwf.edu/stable/10.1163/j.ctt1w8h1gw.9.

Maalouf, Amin. The Crusade Through Arab Eyes. Translated by Jon Rothschild. New York: Schocken Book, 1984.

Murgatroyd, Philip, Bart Craenen, Georgios Theodoropoulos, Vincent Gaffney, John Haldon. “Modeling medieval military logistics: an agent-based simulation of a Byzantine army on the march.” Computational and Mathematical Organization Theory 18, no. 4 (December 2012). https://www-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.uwf.edu/docview/1151418711/abstract/83745F07B5254E69PQ/1?parentSessionId=7knEV8A3mUJVCCXdUFZENF84NSnRbHzFSL146hQ8FnA%3D&accountid=14787&sourcetype=Scholarly%20Journals.

Ovhanesian, Armen. Cilician Armenia and the Crusades. Detroit: Detroit Armenian Cultural Association, 1958. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39076005008581&seq=15.

Peter, DRM. “The Battle for Antioch in the First Crusade (1097-98) according to Peter Tudebode.” De Re Militari, (November 2013). https://deremilitari.org/2013/11/the-battle-for-antioch-in-the-first-crusade-1097-98-according-to-peter-tudebode/

(FofC) Peters, Edward. The First Crusade: The Chronicle of Fulcher of Chartres and Other Source Materials. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1998.

Pryor, John H. Logistics of Warfare in the Age of the Crusades. Routledge, 2016. https://search-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.lib.uwf.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=e000xna&AN=1432428&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

Pryor, John, Elizabeth Jeffreys. The Age of the Dromon: The Byzantine Navy ca 500-1204. Leiden: Brill, 2006. https://web-p-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.lib.uwf.edu/ehost/detail/detail?vid=0&sid=e73916e6-3ca6-4119-bcbf-84e6aa2b5b8a%40redis&bdata=JkF1dGhUeXBlPWlwLHNoaWImc2l0ZT1laG9zdC1saXZlJnNjb3BlPXNpdGU%3d#AN=232517&db=e000xna.

Teall, John L. “The Grain Supply of the Byzantine Empire, 330-1025.” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 13 (1959): 87–139. https://doi.org/10.2307/1291130.

(GF, RofA, SofB) Tylerman, Christopher. Chronicles of the First Crusade. London: Penguin Classics, 2012.

William O’Dell, “Feeding Victory: The Logistics of the First Crusade 1095-1099,” (PhD diss., Western Carolina University, North Carolina, 2020), 46. https://www-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.uwf.edu/docview/2468165075/abstract/8B1C72A57CAE40DFPQ/1.

Usama Ibn Munqidh. The Book of Contemplation: Islam and the Crusades. Translated by Paul M. Cobb. London: Penguin Classics, 2008.

(WofT) William of Tyre. A History of Deeds Done Beyond the Sea, Vol. 1. Translated by Emily Babcock New York: Columbia University Press, 1943. https://hdl-handle-net.ezproxy.lib.uwf.edu/2027/heb06057.0001.001. PDF.

Images

“A Knight of the d’Aluye Family.” In Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Cloisters Collection, 1925. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/470599.

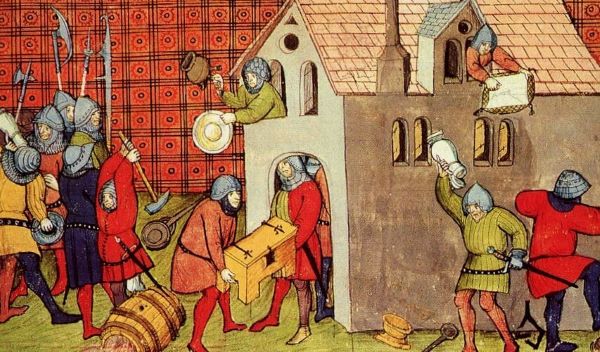

“A 14th-century depiction of the crusaders’ capture of Antioch from a manuscript in the care of the National Library of the Netherlands.” In De Re Militari. https://deremilitari.org/2013/11/the-battle-for-antioch-in-the-first-crusade-1097-98-according-to-peter-tudebode/antiochie_godefroi_robert/.

“Battle of Dorylaeum.” In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Dorylaeum_%281147%29#/media/File:Combat_deuxi%C3%A8me_croisade.jpg.

Paris, Mathew. “A house is pillaged in the 14th century.” In History Maps. https://history-maps.com/article/Logistics-of-European-Medieval-Warfare.

“Scene from the Legend of the True Cross.” In Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Cloisters Collection, 1925. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/470826.

“Alexios I Komnenos.” In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexios_I_Komnenos

Late medieval mail shirt, Syrian or Turkish, now on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.medievalists.net/2019/07/warfare-during-crusades/

“Norman knights from the Bayeux Tapestry.” In World History Encyclopedia. https://www.worldhistory.org/image/8652/bayeux-tapestry-detail-from-battle-of-hastings/

“Seljuq horsemen circa 1063-1092.” In Weapons and Warfare. https://warhistory.org/@msw/article/turkish-seljuk-rule-in-persia-i

Mounted Knight equipment, Siege of Jerusalem (1244 AD). Thom Atkinson. https://www.realmofhistory.com/2016/11/23/10-facts-norman-knights-medieval/

“The fall of the Byzantine frontier.” In HistoryMaps. https://history-maps.com/story/Seljuk-Turks

0 Comments